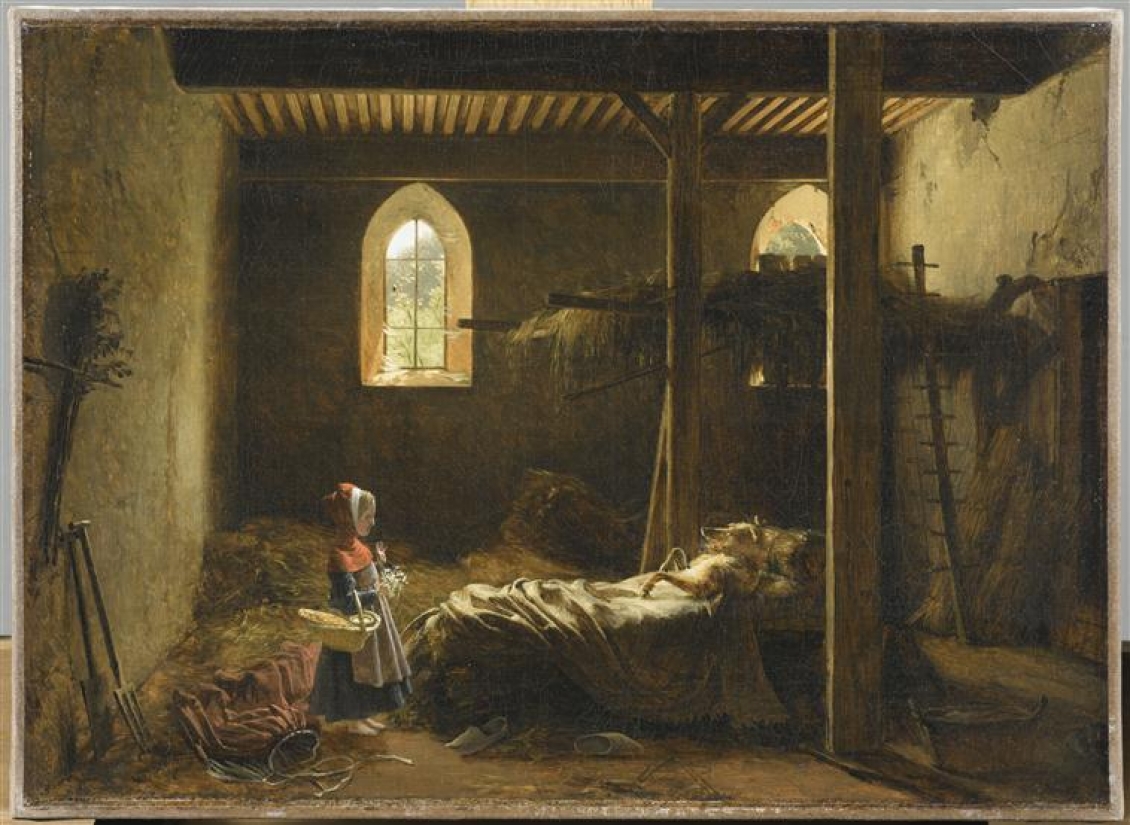

Richard Fleury François, Little Red Hood, 1852, Oil on Paint, Paris, Musée du Louvre © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Michel Urtado

When I was about six, I was at my grandparents’ house in the countryside in the north of the France with my elder sister and cousin. It was the summer, my grandparents were taking a nap and we were hanging out in the garden. My sister was always inventing stories to scare us. Through the window of my grandpa’s workshop, we were able to see into the street. There were three young people and she told us to look at one of them. She said that this redheaded guy at the bus stop has already attacked and threat young girls. He was really young, about 18, but he seemed older at the time. It freaked me out. My sister added that her and my grandpa saw him on the street and he was about to attack a girl. I was really scared and felt trapped in the garden until my grandparents woke up from their nap, I didn’t want to leave the swing.

My sister readapted, in her way, one of Charles Perrault’s many fairy tales, The Little Red Riding Hood. She was my first storyteller of something that has existed for centuries. In the art world, artists have used fairy tales and particularly the figure of the wolf for decades through adaptation, appropriation and re-adaptation just like my sister did. This phenomenon seems to have increased recently with a new generation of artists. For example, Adrien Genty, a French artist, seems to question the figure of the wolf, or more specifically the figure of the little red riding hood through a contemporary adaptation. In his recent series of photos shown last February at Pauline Perplexe, his childhood friend dressed in red clothes stands at the entrance of a suburban park. The boy poses with nonchalance and a trusting look to the camera. He hasn’t yet crossed the woods. He is still in this phase before being an adult and confronted with sexuality. This symbolizes for him, a specific moment of his life when innocence and naivety are still be possible. Genty theatrically captures the moment before puberty and desire. But his friend is already dressed like Little Red Riding Hood and his time to be devoured is close. His switching of the girl-child to a young man is also of note. He has established another image of innocence and the asexual. In other recent artworks, the reference to Little Red Riding Hood is pretty direct. In Alex Wissel’s video In the cellar there is a wolf, the artist stages the child and the wolf in the same body. They are reunited through the artist himself. What seems interesting here is that the perversion and sexuality are much more obvious than in Genty’s artwork. The child is already exchanging kisses with the wolf. She is completely submissive and doesn’t really try to escape. In fact, she can’t because she is inextricably connected to him. Wissel decided to do a video on a stage about this fairy tale. In a text entitled Une vie de chien, Catherine Grenier underlines the relationship between theater, sexuality, and animals: “In the field of sexuality, of course, the animal offers to fantasy an embodiment both theatrical and sarcastically realistic. ” Those artists, through the figure of the wolf in fairytales, serve as an initiation from childhood to adulthood to the perversity of the world but with some distance and sarcasm achieved through simulacra and allegories.

In some other versions in literature, the man turns into a wolf. Although there is currently a renewed interest for that character, the werewolf has long existed in literature, evidenced by an illustration by Cranach of half man-half wolf devouring people in a village (1472-1553) during the Renaissance. The place of the wolf is not the same as in The Little Red Riding Hood. On October 6th, there was a full moon. When this happens each month, it brings me to a specific state of mind. I might be in a bad mood or feel that I have too much energy. The result is always the same, I will have nightmares and not sleep very well. Those nights have a specific kind of light, very strong and sharp. The full moon is also the time when the man turns into a werewolf. On that night, I might change my behavior and become a bad person. I might have sex with strangers, hurt people’s feelings, take some drugs, and drink alcohol. At least, it is a way to see it. The night is full of imagery of decadence and danger. The werewolf has become one of its main figures and has been one of the characters of many stories and tales from mythology to current mainstream books and movies. I see it as something pretty real in the art world: it can be the collector, the gallerist, the assistant, the artist, the curator, or the critic. Throughout History, the werewolf has also been named occasionally the “lycanthrope”. Jean Wier, a doctor in France (1515-1588), explained lycanthropy as an imaginary and pathological phenomenon. Lycanthropy has also been defined as a disease which, over the centuries when demons were seen everywhere, it disturbed weak people, to such an extent that they believed they were turning into werewolves. Melancholic people were more exposed than others. At some point the wolf was the incarnation of madness and the fear of madness. In Lila de Magalhaes’s works, if there is no specific relation directly to wolves, her imagery is full of animals, from insects to cats. In her embroideries or ceramics, you can see the potential humanity, cruelty, and melancholy that haunt the animals. They are full of resentment and always slightly worried. In some ways, in the art world, we are continuously confronted with the fear of becoming mad and turning into a monster because we are playing with our own boundaries and melancholia. What can I write? What can I show? How can I get more exposure? What can I do to be recognized? What can I do to be more personal or to be more individual? As soon as I am trying to touch these questions, I am crossing the line from humanity to animality, perversity, sexuality, and madness, which is maybe the basis of being a good artist.

In that vein, the beast can become your lover. As a critic and curator, I might fall in love with artists, sometimes it is only professional, sometimes I kiss them once, sometimes I spend several years with them. In the tale The Beauty and The Beast, the figure of the wolf came back. The man has been turned into a wolf because of a curse; his only way to get back to his real appearance is to make sure that someone is falling in love with him. But Beauty is much more beautiful than him and first she is his prisoner. She learns to know him and it is through humor and intellectual exchange that they begin to fall in love. Some artists have decided to incarnate themselves into an animal. Through parody and humor, the silly beast becomes loaded in the artworks of many artists. In recent works by Josquin Gouilly Froissard, the question of animality is especially significant. He first started painting on dog sculptures that he found or that people gave to him. When he starts to paint them, he wants to circumvent the initial goal of painting and arrives in this way at actual paintings. At the same time, he began taking self-portraits of himself as a dog, including one of himself as a stuffed dog hanging a brush. There is a form of derision that is reminiscent of artists such as Mike Kelley or Paul McCarthy. Those artists have turned themselves into sarcastic animals. Their bestiality brings me to a form of love that I don’t share with others artists. Maybe just like in Beauty and the Beast, I can only fall in love with a half-artist, half-wolf who acts silly and crazy. It is also maybe a way to accept the world in its absurdity.

In literature, this story has been written for centuries from mythology in Antiquity to storyteller in the Middle Ages and to tales in the 18th century. Through this kind of imagery and fantasy, we reflect on our way to interact with the world and with each other. Some of those figures can disappear and return, as if that kind of characters has always been there and needs to be reinterpreted through the light of a specific era. Tales, myths, and storytellers were teaching people how to react to specific kinds of attitudes or threats. Those threats were often coming from a wolf, a beast or more recently from a werewolf or even a vampire. I think we are in a specific era in which we must think about what can hurt us deeply, what we can share with others. What can we borrow from others? What can link us to each others’ emotions and pain? I guess I always wanted to know: who and where is the wolf? What does he want from me? And where does he come from? Should I follow him? The wolf has come through ages as a threat both in the art world and in literature because he represents our way to inhabit the world.

Bibliography

1. « Sur le terrain de la sexualité, bien sûr, l’animal offre au fantasme une incarnation tout à la fois théâtrale et sarcastiquement réaliste » p.92. Catherine Grenier « Une vie de chien » in La part de l'autre : [Carré d'Art, musée d'art contemporain, Nîmes, du 18 mai au 15 septembre 2002]. Editeur : Arles : Actes Sud Nîmes : Carré d'art, 2002. 159 p

My sister readapted, in her way, one of Charles Perrault’s many fairy tales, The Little Red Riding Hood. She was my first storyteller of something that has existed for centuries. In the art world, artists have used fairy tales and particularly the figure of the wolf for decades through adaptation, appropriation and re-adaptation just like my sister did. This phenomenon seems to have increased recently with a new generation of artists. For example, Adrien Genty, a French artist, seems to question the figure of the wolf, or more specifically the figure of the little red riding hood through a contemporary adaptation. In his recent series of photos shown last February at Pauline Perplexe, his childhood friend dressed in red clothes stands at the entrance of a suburban park. The boy poses with nonchalance and a trusting look to the camera. He hasn’t yet crossed the woods. He is still in this phase before being an adult and confronted with sexuality. This symbolizes for him, a specific moment of his life when innocence and naivety are still be possible. Genty theatrically captures the moment before puberty and desire. But his friend is already dressed like Little Red Riding Hood and his time to be devoured is close. His switching of the girl-child to a young man is also of note. He has established another image of innocence and the asexual. In other recent artworks, the reference to Little Red Riding Hood is pretty direct. In Alex Wissel’s video In the cellar there is a wolf, the artist stages the child and the wolf in the same body. They are reunited through the artist himself. What seems interesting here is that the perversion and sexuality are much more obvious than in Genty’s artwork. The child is already exchanging kisses with the wolf. She is completely submissive and doesn’t really try to escape. In fact, she can’t because she is inextricably connected to him. Wissel decided to do a video on a stage about this fairy tale. In a text entitled Une vie de chien, Catherine Grenier underlines the relationship between theater, sexuality, and animals: “In the field of sexuality, of course, the animal offers to fantasy an embodiment both theatrical and sarcastically realistic. ” Those artists, through the figure of the wolf in fairytales, serve as an initiation from childhood to adulthood to the perversity of the world but with some distance and sarcasm achieved through simulacra and allegories.

In some other versions in literature, the man turns into a wolf. Although there is currently a renewed interest for that character, the werewolf has long existed in literature, evidenced by an illustration by Cranach of half man-half wolf devouring people in a village (1472-1553) during the Renaissance. The place of the wolf is not the same as in The Little Red Riding Hood. On October 6th, there was a full moon. When this happens each month, it brings me to a specific state of mind. I might be in a bad mood or feel that I have too much energy. The result is always the same, I will have nightmares and not sleep very well. Those nights have a specific kind of light, very strong and sharp. The full moon is also the time when the man turns into a werewolf. On that night, I might change my behavior and become a bad person. I might have sex with strangers, hurt people’s feelings, take some drugs, and drink alcohol. At least, it is a way to see it. The night is full of imagery of decadence and danger. The werewolf has become one of its main figures and has been one of the characters of many stories and tales from mythology to current mainstream books and movies. I see it as something pretty real in the art world: it can be the collector, the gallerist, the assistant, the artist, the curator, or the critic. Throughout History, the werewolf has also been named occasionally the “lycanthrope”. Jean Wier, a doctor in France (1515-1588), explained lycanthropy as an imaginary and pathological phenomenon. Lycanthropy has also been defined as a disease which, over the centuries when demons were seen everywhere, it disturbed weak people, to such an extent that they believed they were turning into werewolves. Melancholic people were more exposed than others. At some point the wolf was the incarnation of madness and the fear of madness. In Lila de Magalhaes’s works, if there is no specific relation directly to wolves, her imagery is full of animals, from insects to cats. In her embroideries or ceramics, you can see the potential humanity, cruelty, and melancholy that haunt the animals. They are full of resentment and always slightly worried. In some ways, in the art world, we are continuously confronted with the fear of becoming mad and turning into a monster because we are playing with our own boundaries and melancholia. What can I write? What can I show? How can I get more exposure? What can I do to be recognized? What can I do to be more personal or to be more individual? As soon as I am trying to touch these questions, I am crossing the line from humanity to animality, perversity, sexuality, and madness, which is maybe the basis of being a good artist.

In that vein, the beast can become your lover. As a critic and curator, I might fall in love with artists, sometimes it is only professional, sometimes I kiss them once, sometimes I spend several years with them. In the tale The Beauty and The Beast, the figure of the wolf came back. The man has been turned into a wolf because of a curse; his only way to get back to his real appearance is to make sure that someone is falling in love with him. But Beauty is much more beautiful than him and first she is his prisoner. She learns to know him and it is through humor and intellectual exchange that they begin to fall in love. Some artists have decided to incarnate themselves into an animal. Through parody and humor, the silly beast becomes loaded in the artworks of many artists. In recent works by Josquin Gouilly Froissard, the question of animality is especially significant. He first started painting on dog sculptures that he found or that people gave to him. When he starts to paint them, he wants to circumvent the initial goal of painting and arrives in this way at actual paintings. At the same time, he began taking self-portraits of himself as a dog, including one of himself as a stuffed dog hanging a brush. There is a form of derision that is reminiscent of artists such as Mike Kelley or Paul McCarthy. Those artists have turned themselves into sarcastic animals. Their bestiality brings me to a form of love that I don’t share with others artists. Maybe just like in Beauty and the Beast, I can only fall in love with a half-artist, half-wolf who acts silly and crazy. It is also maybe a way to accept the world in its absurdity.

In literature, this story has been written for centuries from mythology in Antiquity to storyteller in the Middle Ages and to tales in the 18th century. Through this kind of imagery and fantasy, we reflect on our way to interact with the world and with each other. Some of those figures can disappear and return, as if that kind of characters has always been there and needs to be reinterpreted through the light of a specific era. Tales, myths, and storytellers were teaching people how to react to specific kinds of attitudes or threats. Those threats were often coming from a wolf, a beast or more recently from a werewolf or even a vampire. I think we are in a specific era in which we must think about what can hurt us deeply, what we can share with others. What can we borrow from others? What can link us to each others’ emotions and pain? I guess I always wanted to know: who and where is the wolf? What does he want from me? And where does he come from? Should I follow him? The wolf has come through ages as a threat both in the art world and in literature because he represents our way to inhabit the world.

Bibliography

1. « Sur le terrain de la sexualité, bien sûr, l’animal offre au fantasme une incarnation tout à la fois théâtrale et sarcastiquement réaliste » p.92. Catherine Grenier « Une vie de chien » in La part de l'autre : [Carré d'Art, musée d'art contemporain, Nîmes, du 18 mai au 15 septembre 2002]. Editeur : Arles : Actes Sud Nîmes : Carré d'art, 2002. 159 p

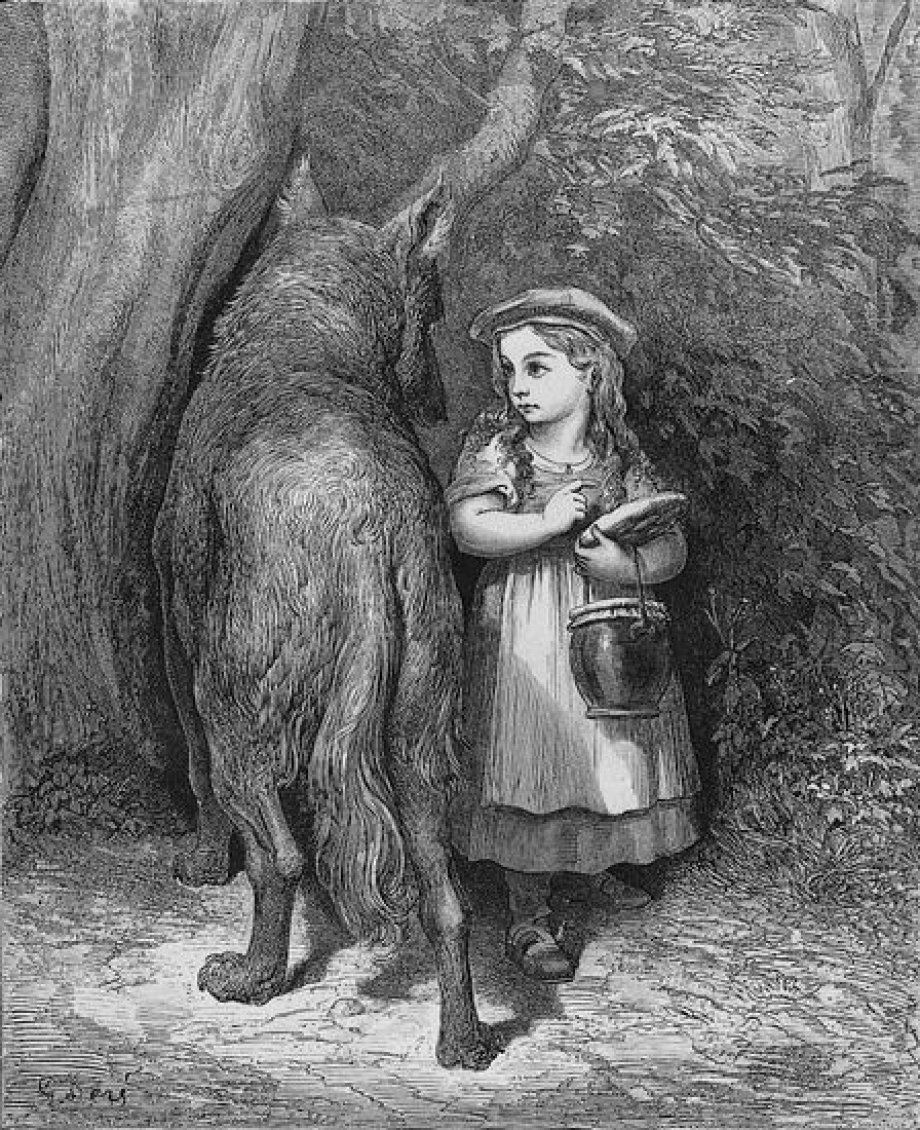

Gustave Doré, The Wolf & Little Red Hood, 1864, illustration, Paris, National Library of France (BNF) © BnF, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / image BnF

Adrien Genty, What happened? (detail), 2017 © Pauline Perplexe

Lucas Cranach The Old, The Werewolf, around 1512, woodcut, 162 × 126 mm, Gotha, Herzogliches Museum © Gotha, Herzogliches Museum

Lila de Magalhaes, Untitled, exhibited at Remote Control, June 2017, Abode Gallery, Los Angeles © Lila de Magalhaes

Josquin Gouilly Froissard, Prick, Silver print, 60x90cm, 2016 © Josquin Gouilly Froissard

03-03-2016

↑