The New-York-based artist, previously exhibited at Extramentale, Jennifer May-Reiland speaks about Lisa Signorini’s characters and style of drawing. Whilst describing her as an “aesthetic dominatrix” who embraces, through her art, love, contempt, drunkenness, mania, humiliation and lust for luxurious objects, May Reiland also builds metaphorically a dialogue between two cities: Paris and New-York, as if the Signorini has turned the spirit of the 70’s New York into a raw material for her own vivid and narrative practice. But Signorini might have dug into different histories too, into various pockets of resistance and lust : those that can’t be told out loud. Lisa Signorini is a born-actress. She is also a born-medium. For her exhibition at E A Shared Space she will showcase a selection of drawings, etching and paintings, leaving outside another aspect of her practice, the video. She lives in Paris and New-York.

Aesthetic Dominatrix

I met Lisa in New York several years ago when she was visiting from Paris. Signorini’s work seems quintessentially New York to me, in its democratic flattening of high and low influences, in its embrace of grime and filth, in its cynicism and sincerity.

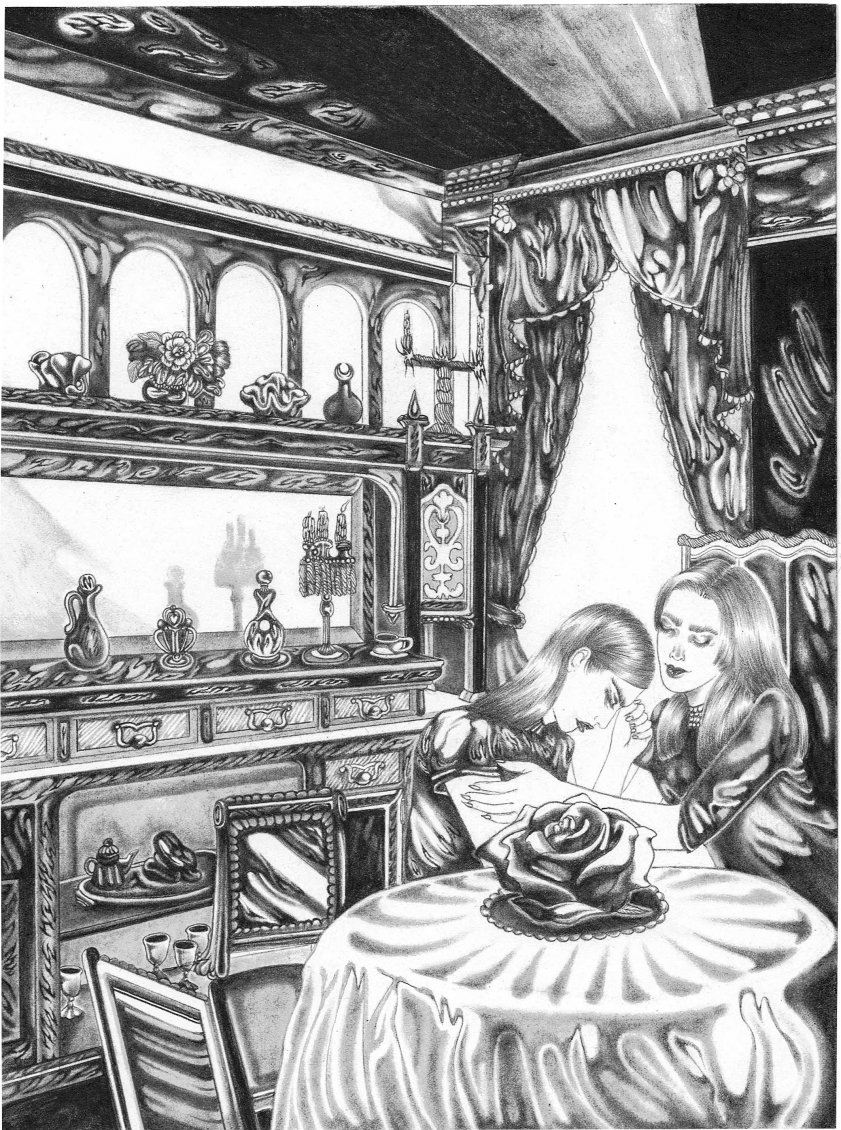

In viewing Signorini’s work, I’m reminded of the classic La maison de rendez-vous by Alain Robbe-Grillet, where time is a cycle, a mannequin is a woman, and a crime (of murder, of lust) happens again and again in slightly varied circumstances while an indifferent public looks on. In Signorini’s drawings, time repeats, and grows queerer: more violent, more naive, more childlike, more sexy.

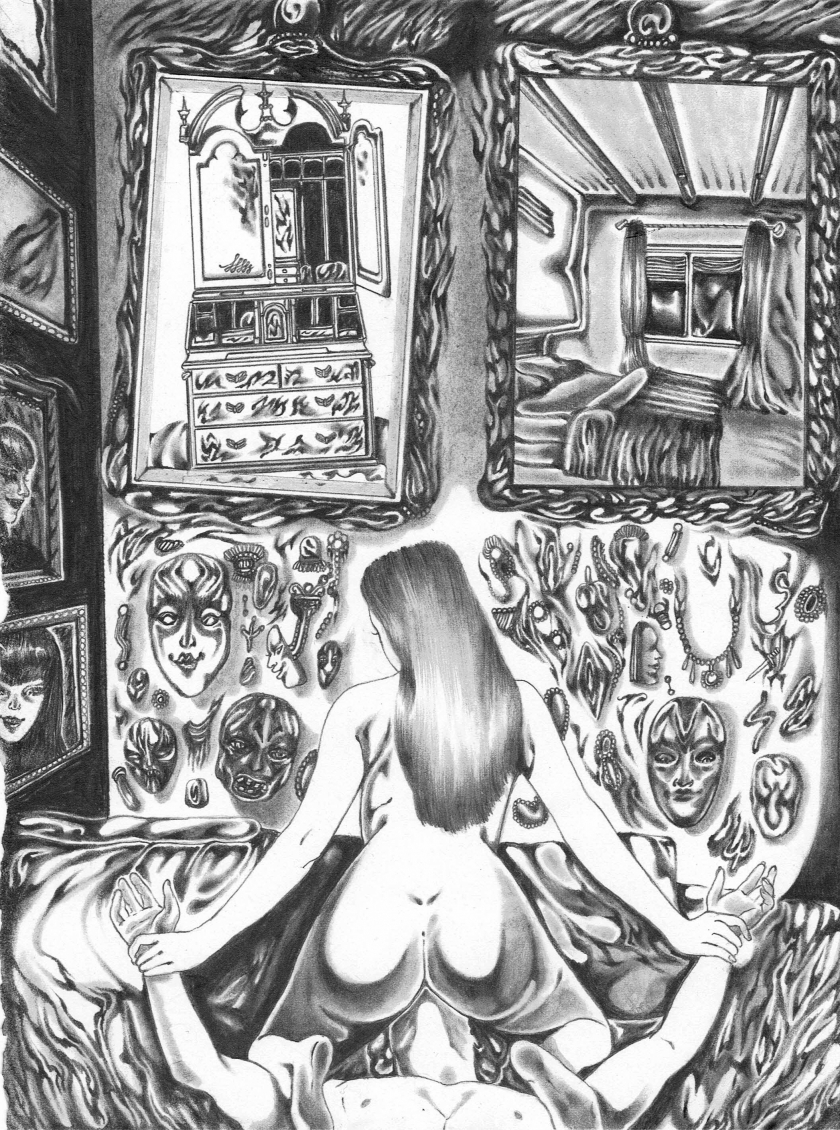

Of course, La maison de rendez-vous also speaks of a very French type of exoticism: orientalism, certainly, but also what we, even in English, call nostalgie de la boue–the concept itself too shameful to be spoken aloud in English. Orientalism, and a kind of equivalent “Newyorkism,” enter Signorini’s work in the form of certain forms, flourishes, details. We might be in a New Yorker’s idea of “the Orient”, or a Parisian’s view of “New York”. Likewise, the characters in her drawings seem animated by nostalgie de la boue. It’s not just that they indulge in vice, although they do. Their environment is shaped by plastic bottles, steel chains, tribal tattoos–some of the most aesthetically reviled objects by which humans have made their mark on nature. There is an attraction for ugliness, for aesthetic degradation.

Is it shameful to be ugly? To like ugly things? Can this shame be aestheticized and enjoyed? I see Signorini as an aesthetic dominatrix, rubbing our noses in the shame of our ugliness–and making us like it.

Unlike many European capitals, New York could be fairly described as ugly. The American tourist in Europe swoons over the pretty and picturesque, while disdaining to spend tax dollars at home for the maintenance and beautification of our own capitals. Which is more shameful? To admire trite beauty? Or to be attracted to ugliness, to filth, to the unsightly detritus of human beings?

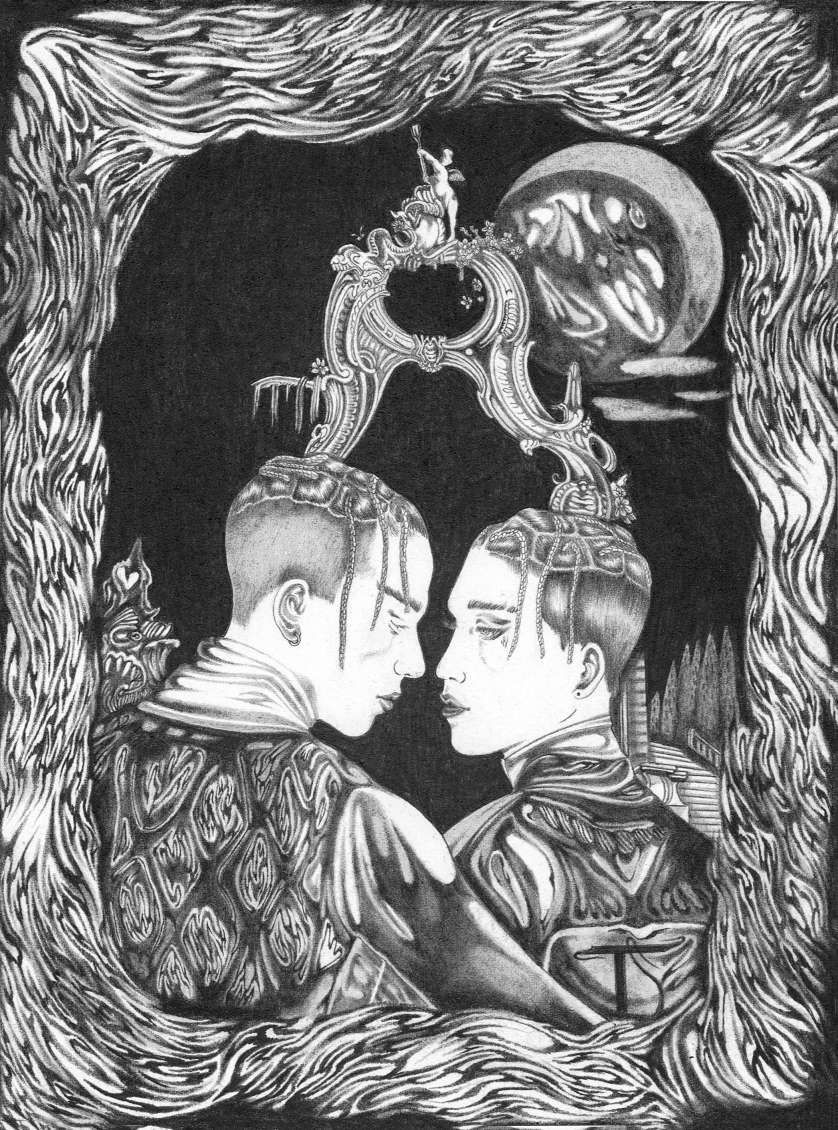

Signorini’s inhuman, sci-fi characters seem to be experiencing real human emotions despite their shining robotic exteriors. Love, contempt, drunkenness, mania, humiliation, lust for luxurious objects. These cyborgs partake of the most shameful human emotions and vices.

Is it human to want to be humiliated? In a world increasingly dominated by cyborgs and algorithms, is the desire to be humiliated just the desire to be human again? In a future where all humans have been replaced by robots, will nostalgie de la boue be experienced by artificial intelligences? Will they long to know what authentic humiliation feels like? Will they long for the sensual experiences humans had with plastic bottles, steel chains, tribal tattoos?

The climax of La maison de rendez-vous, is a live sex show performed before well-heeled colonialists. Again and again, they watch a dog attack a girl, tearing off her clothes onstage.

This scene itself is reminiscent of one of the most viscerally painful in the Marquis de Sade’s work: in Justine, the unhappy Thérèse is tied between four trees and her aristocratic master releases his mastiffs to maul her, covering her body with bites. Signorini’s work recalls Sade’s in its ambivalence of tone–are we to stand respectfully before the technical mastery of her work or laugh at its dark humour? To abhor her cruel masters or admire them? To be aroused or to be disturbed? To consider her drawings ugly or beautiful? Can we liberate ourselves enough to allow ourselves to experience both before her work? To embrace the shameful, degraded, humiliating reality of our humanity. Rats, drugs, plastic bottles, awful tattoos, shameful desires, sexual depravity.

Signorini’s work is above all counter-cultural in its refusal to adopt a consistent tone. Like the 1970s New York world of underground zines, punk album covers, and photocopied porn magazines her aesthetic evokes, her drawings are absolutely sincere while invoking aspects of human nature which are supposed to be shameful. Not just sex or vice, but aesthetics considered “trashy” or un-serious. Signorini takes them seriously and obligates the viewer to do so too. We find ourselves appreciative voyeurs of an insistent aesthetic which seduces us despite ourselves–we are watching the act of violence, of aesthetic transgression, again and again, and liking it.

- Jennifer May Reiland

Aesthetic Dominatrix

I met Lisa in New York several years ago when she was visiting from Paris. Signorini’s work seems quintessentially New York to me, in its democratic flattening of high and low influences, in its embrace of grime and filth, in its cynicism and sincerity.

In viewing Signorini’s work, I’m reminded of the classic La maison de rendez-vous by Alain Robbe-Grillet, where time is a cycle, a mannequin is a woman, and a crime (of murder, of lust) happens again and again in slightly varied circumstances while an indifferent public looks on. In Signorini’s drawings, time repeats, and grows queerer: more violent, more naive, more childlike, more sexy.

Of course, La maison de rendez-vous also speaks of a very French type of exoticism: orientalism, certainly, but also what we, even in English, call nostalgie de la boue–the concept itself too shameful to be spoken aloud in English. Orientalism, and a kind of equivalent “Newyorkism,” enter Signorini’s work in the form of certain forms, flourishes, details. We might be in a New Yorker’s idea of “the Orient”, or a Parisian’s view of “New York”. Likewise, the characters in her drawings seem animated by nostalgie de la boue. It’s not just that they indulge in vice, although they do. Their environment is shaped by plastic bottles, steel chains, tribal tattoos–some of the most aesthetically reviled objects by which humans have made their mark on nature. There is an attraction for ugliness, for aesthetic degradation.

Is it shameful to be ugly? To like ugly things? Can this shame be aestheticized and enjoyed? I see Signorini as an aesthetic dominatrix, rubbing our noses in the shame of our ugliness–and making us like it.

Unlike many European capitals, New York could be fairly described as ugly. The American tourist in Europe swoons over the pretty and picturesque, while disdaining to spend tax dollars at home for the maintenance and beautification of our own capitals. Which is more shameful? To admire trite beauty? Or to be attracted to ugliness, to filth, to the unsightly detritus of human beings?

Signorini’s inhuman, sci-fi characters seem to be experiencing real human emotions despite their shining robotic exteriors. Love, contempt, drunkenness, mania, humiliation, lust for luxurious objects. These cyborgs partake of the most shameful human emotions and vices.

Is it human to want to be humiliated? In a world increasingly dominated by cyborgs and algorithms, is the desire to be humiliated just the desire to be human again? In a future where all humans have been replaced by robots, will nostalgie de la boue be experienced by artificial intelligences? Will they long to know what authentic humiliation feels like? Will they long for the sensual experiences humans had with plastic bottles, steel chains, tribal tattoos?

The climax of La maison de rendez-vous, is a live sex show performed before well-heeled colonialists. Again and again, they watch a dog attack a girl, tearing off her clothes onstage.

This scene itself is reminiscent of one of the most viscerally painful in the Marquis de Sade’s work: in Justine, the unhappy Thérèse is tied between four trees and her aristocratic master releases his mastiffs to maul her, covering her body with bites. Signorini’s work recalls Sade’s in its ambivalence of tone–are we to stand respectfully before the technical mastery of her work or laugh at its dark humour? To abhor her cruel masters or admire them? To be aroused or to be disturbed? To consider her drawings ugly or beautiful? Can we liberate ourselves enough to allow ourselves to experience both before her work? To embrace the shameful, degraded, humiliating reality of our humanity. Rats, drugs, plastic bottles, awful tattoos, shameful desires, sexual depravity.

Signorini’s work is above all counter-cultural in its refusal to adopt a consistent tone. Like the 1970s New York world of underground zines, punk album covers, and photocopied porn magazines her aesthetic evokes, her drawings are absolutely sincere while invoking aspects of human nature which are supposed to be shameful. Not just sex or vice, but aesthetics considered “trashy” or un-serious. Signorini takes them seriously and obligates the viewer to do so too. We find ourselves appreciative voyeurs of an insistent aesthetic which seduces us despite ourselves–we are watching the act of violence, of aesthetic transgression, again and again, and liking it.

- Jennifer May Reiland