Is cruelty rejuvenating?

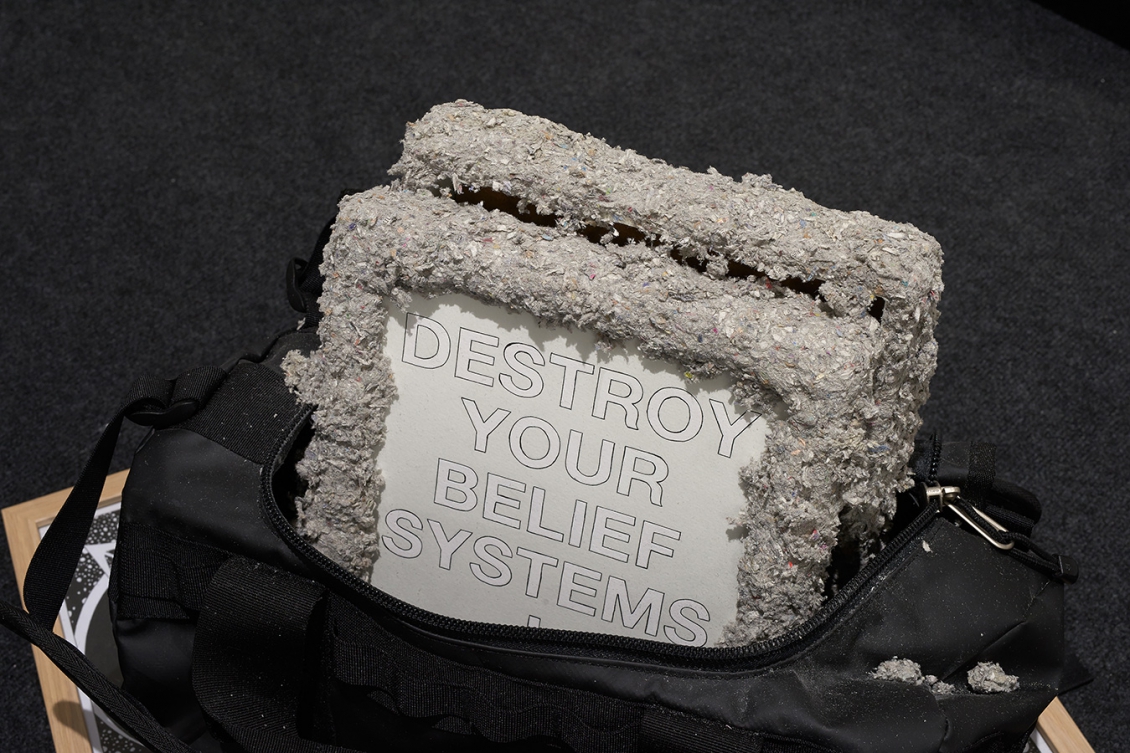

The hundred faces of juvenile cruelty have found their way into this inaugural exhibition. Every work takes us back to stories of insurgents, poètes maudits, lost children, revolutionaries, murderers, geniuses, or simply high schoolers, all of whom have felt the effects of being out of phase with the society into which they were born. Based in Geneva, Paris, or Berlin, the six artists foreground various forms of despair, aimlessness, and violence against the background of fantastic narratives and hard facts. There is no Terrorism problem, there is a problem of REALITY vs FICTION, announces one of the works by Seob Kim Boninsegni. Enclosed in a bubble like a catchphrase or a slogan, it is used to mark a separation, or a misalignment, between the fictional space and the reality.

The horror of wars put the evocative power of fiction to the test, bringing about its obsolescence and the need for its renewal. In the wake of World War II, the doomed humanity thus turned toward its young people. Considered as fountainheads of potential, these underage American consumers would also include society’s poor relatives: the delinquents. The adolescents, today short-changed on their future, were, in the 19th and 20th centuries, the very embodiment of futurity.

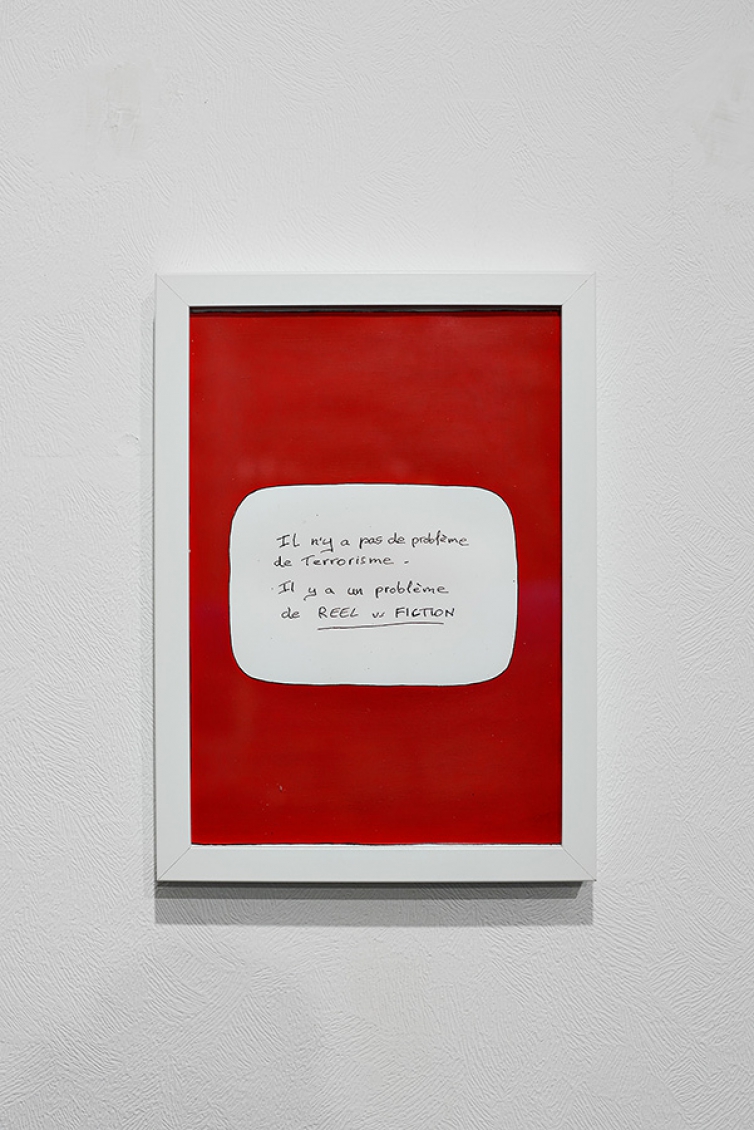

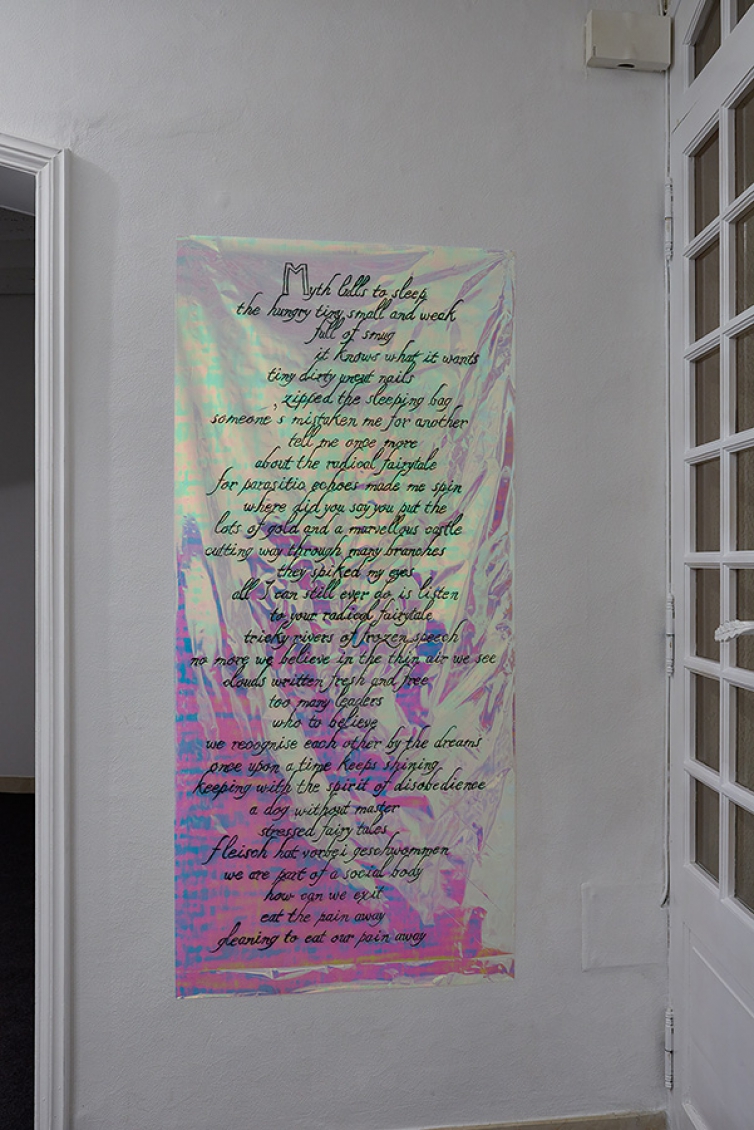

Once upon a time there was an undone bodice of Optimism. Some of the works on display draw on darkness far more ancient than our own age: the darkness of a time that basked in the moral, folk space of the fairy tale. The artists Bianca Benenti and Linda Voorwinde reprise a lithograph by Gustave Doré: one of his illustrations to Perrault’s “Little Tom Thumb.” The only thing that remains of the “Ogre” is the close-up of three faces of the pampered daughters, tucked in their covers, indifferent to leftover bones and to the atrocity of their father’s murderous gesture, which the artists decided to preserve outside the frame. Little Tom Thumb is the same age as the children that, we suppose, are lying asleep or slaughtered. He had sacrificed the gang of ogresses in order to come closer to his true fraternal community — a bond that is signaled by the use of a section of a diseased tree trunk cut into the shape of a bandana. Overall blue, the bandana signals allegiance to a gang. Is this a pre-adult world or a community whose common denominator is a shared craving for cruelty and cultural goods? The Hollywood machine and American society have fueled runaway dreams of teenagers who are trapped in orbiting bubbles. Fantasy films, pop music and its gravitation toward counterculture before becoming mainstream, all promote escapism, a sense of belonging and/or a turn to horror. Little blue-colored horror: Bluebeard with baby fuzz around his chin.

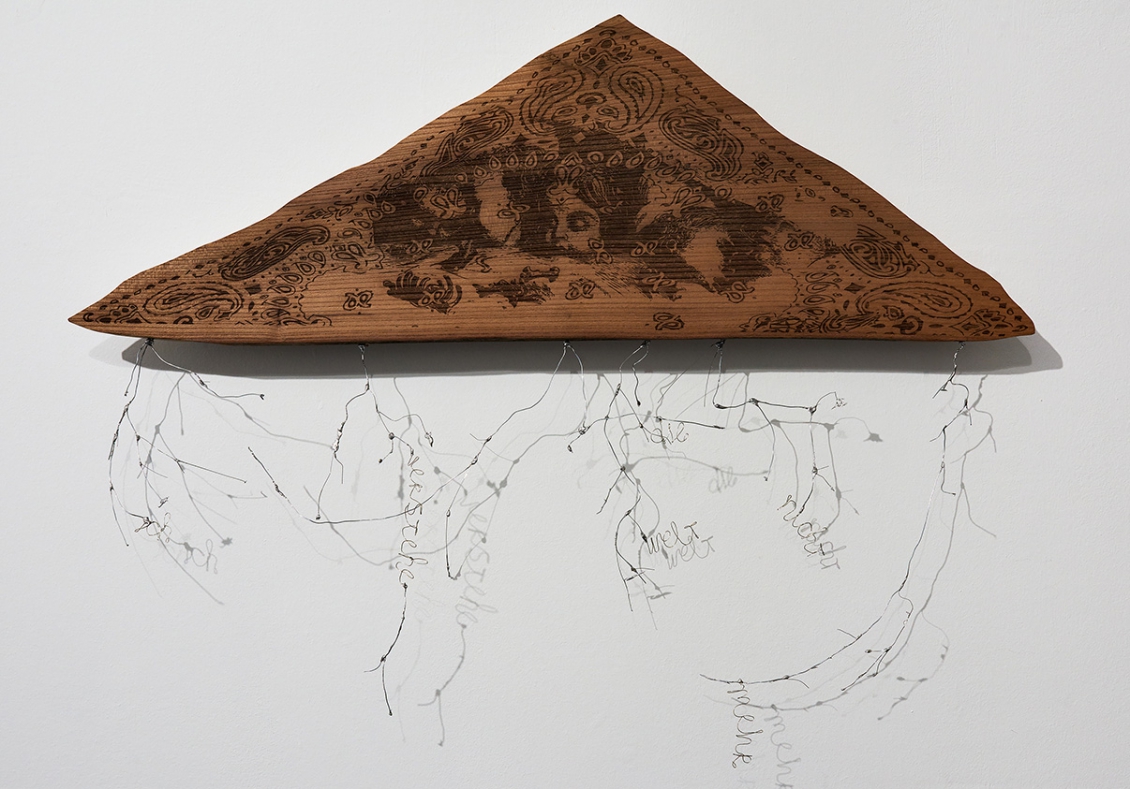

Harry Potter’s hat, imagined by the collective Real Madrid, traveled through time, changed its chroma, its popularity, and its skin: it is paint, it is blue, it is a radio playing five summer hits.

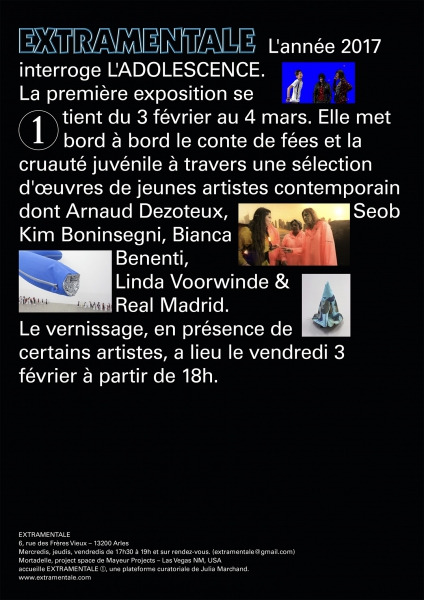

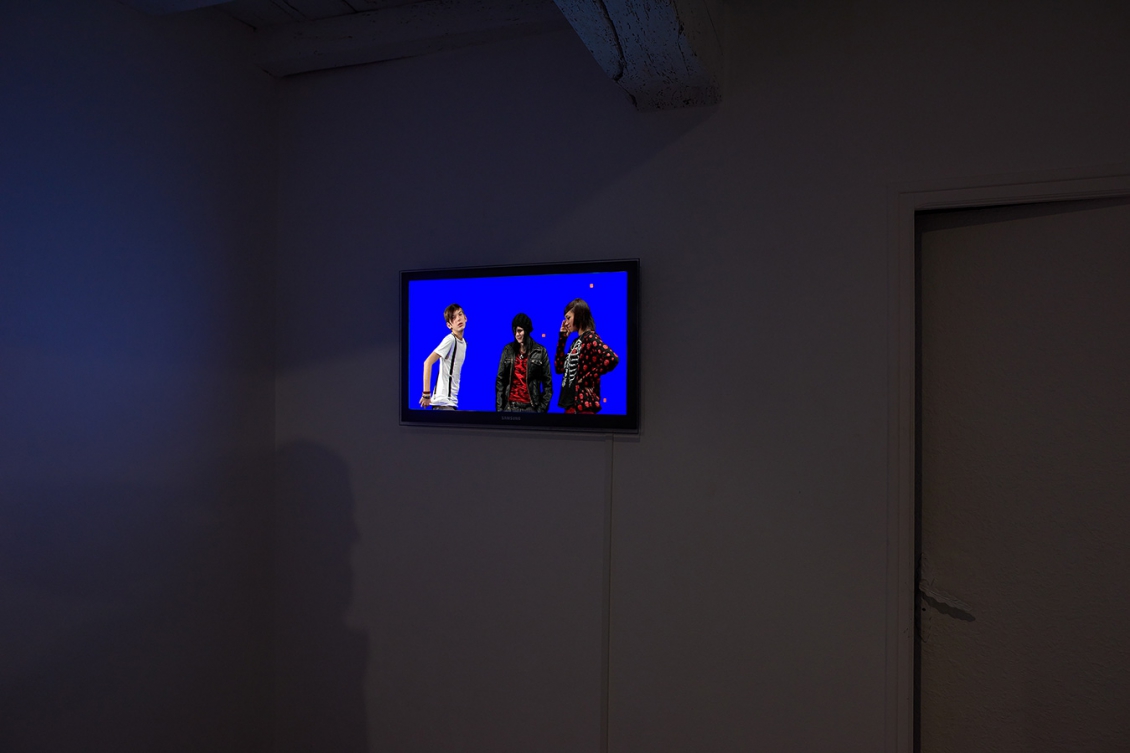

So the color blue triumphs. The curvy, fluid form, by Boninsegni, floats through space like ectoplasm, deformed and bloated. Emanating from our dreams, this sculpture is in reality a material transposition of the energy beam radiating from the stomach of the schizophrenic teenager in the fantasy film Donnie Darko. The color blue is also the blank page that summons the imagination in the film HABIB/KELLY/EMILIE by Arnaud Dezoteux. That blue sheet brings together the beginner’s enthusiasm and the producer’s active voyeurism as the camera surreptitiously captures the vacuity of the scenes featuring three teenagers against a blue background. The effect of being out of phase, described earlier, is here reinforced by the strange character of this situation in which non-professional actors are struggling to immerse themselves in their acoustic environment. TACTILLAS BONUS, filtered through chroma keying, this is the second part of Dezoteux’s film installation, produced while he was still a student.

The hundred faces of juvenile cruelty have found their way into this inaugural exhibition. Every work takes us back to stories of insurgents, poètes maudits, lost children, revolutionaries, murderers, geniuses, or simply high schoolers, all of whom have felt the effects of being out of phase with the society into which they were born. Based in Geneva, Paris, or Berlin, the six artists foreground various forms of despair, aimlessness, and violence against the background of fantastic narratives and hard facts. There is no Terrorism problem, there is a problem of REALITY vs FICTION, announces one of the works by Seob Kim Boninsegni. Enclosed in a bubble like a catchphrase or a slogan, it is used to mark a separation, or a misalignment, between the fictional space and the reality.

The horror of wars put the evocative power of fiction to the test, bringing about its obsolescence and the need for its renewal. In the wake of World War II, the doomed humanity thus turned toward its young people. Considered as fountainheads of potential, these underage American consumers would also include society’s poor relatives: the delinquents. The adolescents, today short-changed on their future, were, in the 19th and 20th centuries, the very embodiment of futurity.

Once upon a time there was an undone bodice of Optimism. Some of the works on display draw on darkness far more ancient than our own age: the darkness of a time that basked in the moral, folk space of the fairy tale. The artists Bianca Benenti and Linda Voorwinde reprise a lithograph by Gustave Doré: one of his illustrations to Perrault’s “Little Tom Thumb.” The only thing that remains of the “Ogre” is the close-up of three faces of the pampered daughters, tucked in their covers, indifferent to leftover bones and to the atrocity of their father’s murderous gesture, which the artists decided to preserve outside the frame. Little Tom Thumb is the same age as the children that, we suppose, are lying asleep or slaughtered. He had sacrificed the gang of ogresses in order to come closer to his true fraternal community — a bond that is signaled by the use of a section of a diseased tree trunk cut into the shape of a bandana. Overall blue, the bandana signals allegiance to a gang. Is this a pre-adult world or a community whose common denominator is a shared craving for cruelty and cultural goods? The Hollywood machine and American society have fueled runaway dreams of teenagers who are trapped in orbiting bubbles. Fantasy films, pop music and its gravitation toward counterculture before becoming mainstream, all promote escapism, a sense of belonging and/or a turn to horror. Little blue-colored horror: Bluebeard with baby fuzz around his chin.

Harry Potter’s hat, imagined by the collective Real Madrid, traveled through time, changed its chroma, its popularity, and its skin: it is paint, it is blue, it is a radio playing five summer hits.

So the color blue triumphs. The curvy, fluid form, by Boninsegni, floats through space like ectoplasm, deformed and bloated. Emanating from our dreams, this sculpture is in reality a material transposition of the energy beam radiating from the stomach of the schizophrenic teenager in the fantasy film Donnie Darko. The color blue is also the blank page that summons the imagination in the film HABIB/KELLY/EMILIE by Arnaud Dezoteux. That blue sheet brings together the beginner’s enthusiasm and the producer’s active voyeurism as the camera surreptitiously captures the vacuity of the scenes featuring three teenagers against a blue background. The effect of being out of phase, described earlier, is here reinforced by the strange character of this situation in which non-professional actors are struggling to immerse themselves in their acoustic environment. TACTILLAS BONUS, filtered through chroma keying, this is the second part of Dezoteux’s film installation, produced while he was still a student.